There’s an interesting study on postdocs out today, from the Canadian Association of Postdoctoral Scholars (CAPS) and MITACS. The report provides a wealth of data on postdocs’ demographics, financial status, likes, dislikes, etc. It’s all thoroughly interesting and well worth a read, but I’m going to restrict my comments to just two of the most interesting results.

The first has to do, specifically, with postdocs’ legal status. In Quebec, they are considered students. Outside Quebec, it depends: if their funding comes from internal university funds, they are usually considered employees; but, if their funding is external, they are most often just “fellowship holders” – an indistinct category which could mean a wide variety of things in terms of access to campus services (are they students? Employees? Both? Neither?). Just taxonomically, the whole situation’s a bit of a nightmare, and one can certainly see the need for greater clarity and consistently if we ever want to make policy on postdocs above the institutional level.

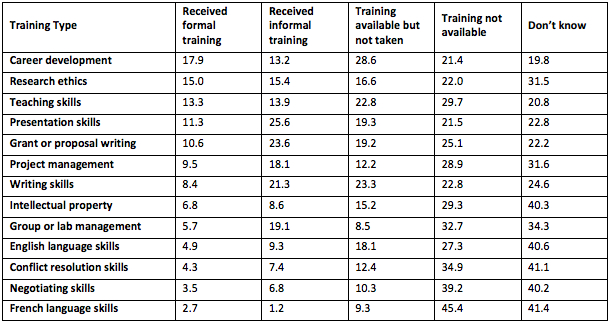

The second – somewhat jaw-dropping – point of interest is the table on page 27, which examines postdocs’ training.

Level of Training Received or Available, in % (The 2013 Canadian Postdoc Survey, Table 3, pg. 27)

As the authors note, being trainees is what makes postdocs a distinct group – it’s basically the only thing that distinguishes them from research associates. So what should we infer from the fact that only 18% of postdocs report receiving any formal training for career development, 15% for research ethics, and 11% on either presentation skills or grant/proposal writing? If there’s a smoking gun on the charge that Canadian universities view postdocs as cheap academic labour, rather than as true academics-in-waiting, this table is it.

All of this information is, of course, important; however, this study’s value goes beyond its presentation of new data. One of its most important lessons comes from the fact that a couple of organizations just decided to get together and collect data on their own. Too often in this country, we turn our noses up at anything other than the highest-quality data, but since no one wants to pay for quality (how Canadian is that?), we just wring our hands hoping StatsCan will eventually sort it out it for us.

But to hell with that. StatsCan’s broke, and even when it had money it couldn’t get its most important product (PSIS) to work properly. It’s time the sector got serious about collecting, packaging, and – most importantly – publishing its own data, even if it’s not StatsCan quality. This survey’s sample selection, for instance, is a bit on the dodgy side – but who cares? Some data is better than none. And too often, “none” is what we have.

CAPS/MITACS have done everyone a solid by spending their own time and money to improve our knowledge base about some key contributors to the country’s research effort. They deserve both to be commended and widely imitated.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post