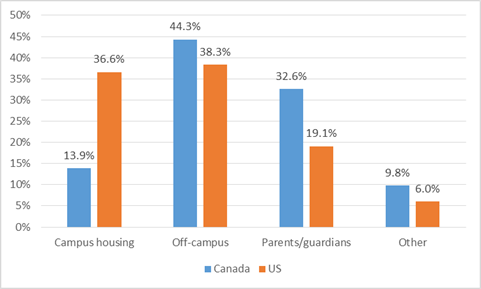

The other day I published a graph on student housing in Canada and the United States that seemed to grab a lot of people’s attention. It was this one:

Figure 1: Student Living Arrangements, Canada vs. US

People seemed kind of shocked by this and wondered what causes the differences. So I thought I’d take a shot at answering this.

(caveat: remember, this is data from a multi-campus survey and I genuinely have no idea how representative this is of the student body as a whole. The ACHA-NCHA survey seems to skew more towards 4-year institutions than the Canadian sample, and it’s also skewed geographically towards western states. Do with that info what you will)

Anyways, my take on this is basically that you need to take into consideration several centuries worth of history to really get the Canada-US difference. Well into the nineteenth century, the principal model for US higher education was Cambridge and Oxford, which were residential colleges. Canada, on the other hand, looked at least as much to Scottish universities for inspiration, and the Scots more or less abandoned the college model during the eighteenth century. This meant that students were free to live at home, or in cheaper accommodations in the city, which some scholars think contributed to Scotland having a much more accessible system of higher education at the time (though let’s not get carried away, this was the eighteenth century and everything is relative).

Then there’s the way major public universities got established in the two countries. In the US, it happened because of the Morrill Acts, which created the “Land-Grant” Universities which continue to dominate the higher education systems of the Midwest and the South. The point of land-grant institutions was to bring education to the people, and at the time, the American population was still mostly rural. Also, these new universities often had missions to spread “practical knowledge” to farmers (a key goal of A&M – that is, agricultural and mechanical – universities), which tended to support the establishment of schools outside the big cities. Finally, Americans at the time – like Europeans – believed in separating students from the hurly-burly of city life because of its corrupting influence. The difference was that Europeans achieved usually achieved this by walling off their campuses (e.g. La Sapienza in Rome), while Americans did it by sticking their flagship public campuses out in the boonies (e.g. Illinois Urbana-Champaign). And as a result of sticking so many universities in small towns, a residential system of higher education emerged more or less naturally.

In Canada, none of this happened because the development of our system lagged the Americans’ by a few decades. Our big nineteenth-century universities – Queen’s excepted – were located in big cities. Out west, provincial universities, which were the equivalent of the American land-grants, didn’t get built until the population urbanized, which is why the Universities of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta are in Winnipeg, Saskatoon and Edmonton instead of Steinbach, Estevan and Okotoks. The corollary of having universities in big cities was that it was easier to follow the Scottish non-residential model.

The Americans could have ditched the residential model during the transition to a mass higher education in the 1950s, but by that time it had become ingrained as the norm because it was how all the prestigious institutions did things. And of course, the Americans have some pretty distinctive forms of student housing too. Fraternities and sororities, often considered a form of off-campus housing in Canada, are very much part of the campus housing scene in at least some parts of the US (witness the University of Alabama’s issuing over $100 million in bonds to spruce up its fraternities).

In short, the answer to the question of why Americans are so much more likely to live on campus than Canadian students is “historical quirks and path dependency”. Given the impact these tendencies have on affordability, that’s a deeply unsatisfying answer, but it’s a worthwhile reminder that in a battle between sound policy and historical path dependency, the latter often wins.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

One last factor, in the 60’s and early 70’s in the US there was a mass influx of public money that was used to build residences (which certainly would not happen now – hello P3’s). While many residences were built in this timeframe within Canada, we also have quite a few institutions that were only just opening or not even opened at this time and public money for residences was unusual at best.

It will be interesting to see what happens to those buildings, now 50-65 years old. Renovation or knock-down? Replacing with P3 buildings or self-financed? How much will P3 residences on campus happen at Canadian universities – it has been common at Ontario colleges but few Universities have dipped a toe in that water here while it becomes more the norm in the US. What will be the impact of improved transit and high-speed trains on choice of institution and where to live?

Thanks for putting up the article.

interesting…

also, FYI the canadian sample tends to be deeply skewed, as each institution sets its own sample, both in composition and in size, often with significant oversamples for subpopulations (e.g. graduate students, international). The ACHA just sort of lumps them all together, regardless of whether the resulting grouping is representative. That may work out in the wash in the states with enough participating institutions, but the canadian one not so much.

One other factor is the number of schools in the US that have a live-on requirement. The school will require students to live on campus for their freshman and sometimes their sophomore year.

Some Canadian schools have a first-year guarantee but not a live on requirement.

This is from the idea to create the community / college on the hill away from distractions as students who spend more time in activities connected to their academics, tend to do better. It also helps ensure the financial feasibility of Residence.