For the last few years, I have been remarking on how long it is taking for graduate incomes to bounce back after the recession of the late 2000s. Well, now there seems to be some evidence that things are finally heading back towards their pre-recession norms.

I am looking at Ontario data only (as I do every year), but Ontario contributes almost half of all university graduates in the country, so this is a pretty good proxy for national numbers. Quebec and BC do also provide university graduate employment/income numbers, but in a way that is very difficult to aggregate with the Ontario numbers (different fields of study definitions, basically); Alberta also puts out graduate employment data, but it doesn’t distinguish between college and university graduates when doing so. So Ontario it is.

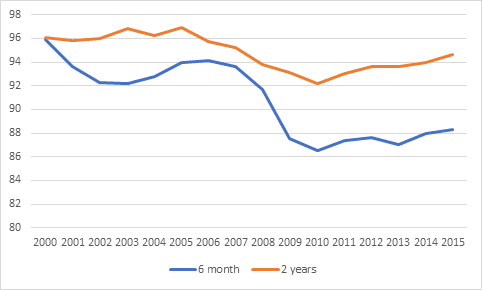

Anyways, the annual government-sponsored graduates survey, released by the Council of Ontario Universities, came out last month. The key data, shown below in Figure 1, shows that the class of 2015 saw a small but real uptick in employment rates six and twenty-four months after graduation; that said, what doesn’t seem to be changing is the gap between those two employment rates, meaning that one of the most lasting changes of the recession is lengthening of the time it takes to land a first job.

Figure 1: Employment Rates of Bachelor’s Graduates 6 months and 2 years after Graduation, classes of 2000 to 2015

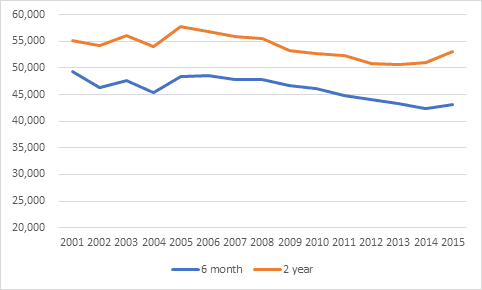

Figure 2 shows incomes at six months and two years after graduation, expressed in inflation-adjusted dollars. What the data shows is that the class of 2015’s incomes were higher than the class of 2014 – the first significant rise since the class of 2005 (which was the last one to have passed the 2-year mark before the great recession of 2008 really started).

Figure 2: Mean Incomes of Bachelor’s Graduates 6 months and 2 years After Graduation in constant $2016, classes of 2001 to 2015

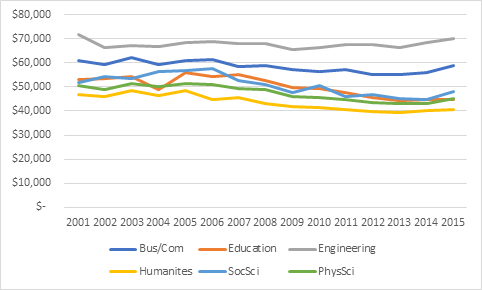

As figure 3 shows, those increases were quite broadly spread – in fact, all six of the major fields of study saw real increases in graduate salaries two years out. Some of those increases were admittedly pretty small, but again it is the first time in a decade that all six major fields saw a real increase in the same year.

If you look at the major fields of study, in fact

the patterns are remarkably similar: with the exception of Engineering where

graduate income has been relatively stable over the past decade, all the major

fields show significant declines over the past decade. The decline differs

somewhat by field of study, but the direction is unmistakeable – down ten

percent since 2005 in business, seventeen in social sciences, nineteen in humanities,

and twenty-one and twenty-three percent in education and physical science,

respectively. That said, only engineers’ incomes are up over that decade;

salaries in education are down 20%, 15 and 16% in social sciences and

humanities, 12% in the physical sciences while in business and commerce they

are about even.

Figure 3: Mean Incomes of Bachelor’s

Graduates 2 Years After Graduation, by Selected Major Field of Study, in

constant $2016, classes of 2001 to 2015

One last point to make here is to note that in most fields of study, the downturn in incomes actually preceded the recession by a couple of years. There’s an important reason for that; namely, that the famous “double-cohort”, created by the elimination of the system of Ontario Academic Credits which effectively acted as a fifth year of secondary after middle school, started graduating in 2006 and 2007. This flooded the market with new graduates, which likely temporarily decreased graduate wages just before the recession hit. Institutions’ decisions to ramp up enrolments to keep graduating classes large in the wake of the double cohort kept supply very high just at a time when demand was weakening. In other words, there were some structural factors at work other than just weak economic demand.

It’s probably too early to declare victory yet: this could just be a one-off. It would be better to wait another year or two before declaring that the graduate labour market is finally returning to pre-2008 norms. Nevertheless, this is the best news we’ve had in some time.