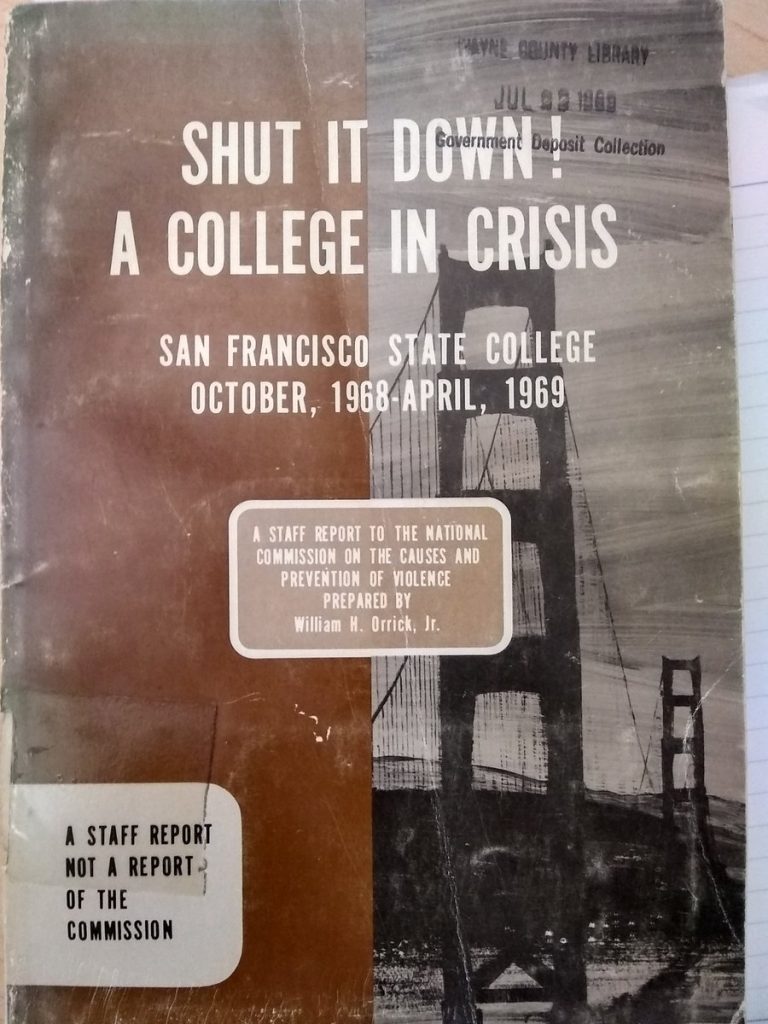

It’s Friday, so it seems like a good day to write about one of the crazy books I have on my shelves (which, as any of my staff can tell you, is a theme that could last for quite some time). Here’s one that’s kind of relevant, given that it’s about an event that ended 50 years ago next week: Shut It Down! A College in Crisis, which is about the strike at San Francisco State (SFS) College in 1968-1969.

The book is, technically, not a work of commercial non-fiction. In mid-1968, in response to the Kennedy and King assassinations and a nationwide series of race riots the previous summer (basically, season six of Mad Men) US President Johnson set up a Presidential Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence (Nixon extended the life of the Commission into late 1969). This being the hip and groovy sixties, before politicians had got the hang of “message discipline”, this Commission not only published reports periodically, it also published several staff reports (that is, research reports written by commission staff as inputs into the Commission process). Nowadays, you’d have to FOI that sucker and wait several years to see anything, but back then they were turned into mass-market paperbacks. This book is one of those staff reports.

The strike at San Francisco State was superficially about curriculum and access; more accurately, it was about the place of racial/ethnic minorities in white liberal institutions. The immediate cause of the strike, which began in the dying days of the 1968 election campaign that would bring Richard Nixon to power, was the case of George Murray, a graduate student & sessional lecturer at SFS who also happened to be the Black Panthers’ Minister of Education. Murray gave a set of inflammatory speeches regarding Black Power in higher education, which included the suggestion that minority students should go around armed in order to protect themselves from racist administrators, and memorably, that “power flows from the barrel of a gun…if you want campus autonomy, if the students want to run the college and the cracker administrators don’t go for it, then you control it with the gun”.

(The 60s were different.)

Campus administrators were inclined to leave Murray alone, fearing a harsh reaction from students. But under pressure from college trustees and the Mayor of San Francisco (who wanted Murray arrested), the radical adjunct professor was suspended on November 1. On November 5, the day of the Presidential election, the Black Student Union issued ten “non-negotiable demands”, about half of which involved the expansion and strengthening of the black studies department (capital Bs were not yet in use), with the remainder having to do with open admissions criteria for black students, reinstating Murray, getting one particular white person fired from the Financial Aid office and replaced with a black person (I have never been able to figure out exactly what the animus was towards this particular woman), and protecting all striking staff and students from retribution. These demands would later be augmented with the demands of what was then called the “Third World Liberation Front” (but which today might be called a Latinx society) which similarly called for major investments in “ethnic studies” and open admissions for all non-whites.

The next day – hours after Nixon was elected – the strike began, with radical students going from one building to another to try to disrupt classes. The administration shut down the campus for a day but opened it again the next day. The students attempted to set up a hard picket and there was violence both on the lines and in the campus itself as striking students engaged in various acts of vandalism. A ham-handed police tactical deployment a week later led to an afternoon of chaos and, subsequently, the closing of the campus for nearly two months. It was re-opened in a limited fashion in mid-January, and the strike ended in March after the administration made concessions to students around black and ethnic studies and admissions criteria but refused to budge on re-hiring Murray or firing the financial aid officer.

(There is some compelling footage of the strike, including the confrontations with police, available on YouTube, here. Worth your time.)

I don’t have a good sense of how historians view this strike in the overall context of American student radicalism. It was, I believe, the longest student strike in American history, though as campus protests went it was nowhere near the most iconic (probably Columbia ’68 or Cornell ‘69) nor the most violent (that would be the Kent State shootings, where four students were killed by the Ohio National Guard). It was certainly one of the first instances of Black Studies achieving the academic status of being a major department, though oddly enough the Wikipedia page devoted to the history of African-American studies spends more time discussing the development of such programs in the U California system than it does at the SFS. In some respects it is more interesting as an episode of radical movements amongst African-Americans than as an episode in student unrest, coming as it did at a period when the Panther Party was expanding nationally but at a low ebb in its cradle, the Bay Area, due to Huey Newton’s manslaughter conviction and Eldridge Cleaver having fled to Cuba (from whence he would head to Algiers to be a full-time revolutionary in exile – and if you want more on that remarkable part of the story, I can highly recommend Algiers, Third World Capital by Elaine Mokhtafi).

But I think one lesson of the story is this: the biggest upsurges against the old order usually come not where the order is manifesting itself in a particularly heinous fashion but rather wherever the radicals happen to congregate. If that’s a conservative school, fine; if it’s at a more or less liberal one, so be it. Just ask anyone at York.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post