I regularly give the Canadian Federation of Students a hard time for advocating policies which are objectively regressive. But fair play to them: in advocating these policies, they are reflecting the actual preferences of students themselves.

A few years ago, we at HESA produced a wide-ranging student survey for a group of student associations. One of the questions asked and how students thought student aid should be awarded. While it would be improper to release results without authorization from a client, the Ontario Undergraduate Student Association published the entire set of results for their members. Since their results are reasonably representative of English Canada as a whole, it’s possible to generalize from these results to the rest of the country.

Survey participants were posed the following scenario:

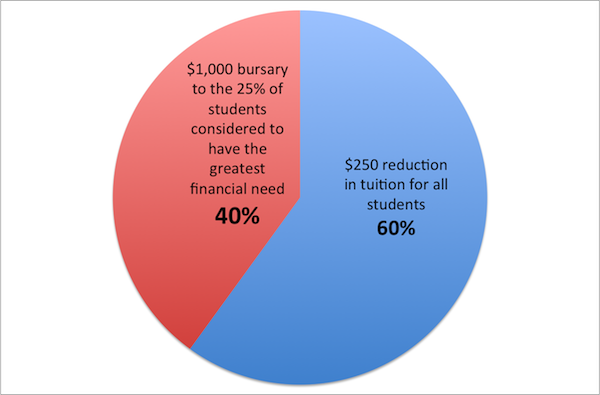

Your provincial government has a small windfall of cash to spend on students in next year’s budget. Which of the following two options comes closest to being your preferred option of how to distribute the money?:

A) A $250 reduction in tuition for all students

B) A $1,000 bursary to the 25% of students considered to have the greatest financial need

Governments face this question all the time: should benefits be targeted or universal? Here’s how students answered it:

Student Preferences for Distribution of Benefits

Got that? Students either don’t trust need assessment calculations, or they genuinely think everyone is equally deserving of aid. In case you’re wondering, it’s not just a selfishness thing; even among students who receive government aid, a majority chose Option A over Option B.

Here’s my explanation: policy-types like me tend to look at affordability as an input into accessibility; that is, we think about policy changes in terms of how they affect people who aren’t in post-secondary education. But students – who by definition don’t need to worry personally about access because they’re already enrolled – view affordability as a pure matter of spending power. Thus, for them, the egalitarian imperative of helping youth who can’t get into PSE is trumped by the (to them) egalitarian imperative of ensuring that student incomes rise broadly. In a way that’s actually a vote of confidence in current student aid programs because it means students believe that living standards are already more or less equal between those with student aid and those without.

It’s understandable why students would take this view, and it’s understandable why a student union would push for a policy which represents its members’ views and makes as little distinction between its members as possible – that, after all, is what unions do.

It’s still no justification, though, for dressing up the demand in spurious and patently false nonsense about access. Just because a policy is popular doesn’t make it smart.