A lot of hypotheses about the negative effects of student debt (some of which I was responsible for, 15 or so years ago), have, over time, been shown to be wrong. The one about debt being a serious deterrent to access, for instance (at least at current levels of borrowing); or the one about how increased student debt delays family formation. But what about the hypothesis that higher levels of student debt might leading students to take “jobs that pay a lot of money” rather than “jobs that are socially useful”?

One paper which seemed to confirm this hypothesis was Constrained After College: Student Loans and Early Career Occupational Choices by Jesse Rothstein and Cecilia Rouse. Using administrative, financial and alumni data from an “anonymous university” (blatantly obviously Princeton), the authors examined the effects on employment of an institutional aid reform which saw loans replaced entirely with grants. They found that after the policy switch, students who received aid took jobs with lower average incomes, while students who were not on aid saw no change in their income patterns. Most of the action happened at the bottom end of the scale – there was no reduction in the proportion going on to investment banking and consulting – the shift was mainly from lower-paying private sector jobs into the non-profit sector.

This is an excellent paper, but still – it’s Princeton. Can you really generalize from that kind of sample?

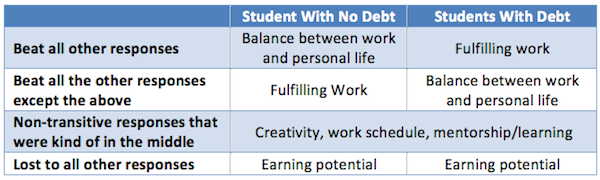

We thought we’d attack the question from another angle by asking students what they will be looking for in a job after graduation: earning potential, balance between work and personal life, fulfilling work, mentorship and learning possibilities, work involves creative rather than routine tasks, flexible working schedule. Then we paired the different options against each other and asked students to tell us which they preferred (matched pairs are a great way to reveal preferences). Finally we looked at how students answered the question based on whether or not they had loans. If the debt hypothesis is true, then you’d expect loan recipients to sacrifice all that good stuff for a job with a higher earnings potential

Here’s how it turned out:

Interesting, huh? And yeah, we checked – the result doesn’t change the closer students get to graduation (and accumulate more debt).

Now maybe the real effect happens in the few months after graduation when they’re suddenly confronted with the reality of paying back loans (though CSL’s various income-contingent features should mitigate that at least somewhat). But as they head out into the workforce there’s little evidence that a preoccupation with earnings is, at present at least, a major outcome of student indebtedness.

One Response