Various bits of labour market paranoia have been driving PSE policy lately. The “skills shortage” is one – even if the case for its actual existence is pretty weak. Another, though, is the broader idea that we’re about to hit a major labour shortage as boomer retirements… well, boom. Time to explore that idea a bit.

At the heart of the labour market shortage meme – popularized mainly by Rick Miner in papers such as, People Without Jobs, Jobs Without People, and Jobs of the Future – is the uncontroversial point that the core-working age population (25-54 year-olds) is shrinking as a percentage of the overall population. As a result, even as population increases, there will be fewer potential workers, hence causing labour shortages, hence leading wages to rise and (though nobody says this part) sending productivity growth into the trash can. Scary stuff.

But it’s worth examining in more detail how Miner developed his scenario. To derive labour market demand, he used 2006 HRSDC data on employment growth to arrive at both a 2011 baseline and a 2015 projection, and then assumed that subsequent growth would continue at a pace roughly equal to HRSDC’s 2011-15 projection (0.8% per year). To derive labor market supply, he applied “current” (the base year is unclear) rates of participation by age group, and applied them forward to 2031. These estimates produced a potential demand of 21.1 million jobs, and a supply (using his “medium estimates”) of about 18.4 million – a deficit of 2.7 million jobs.

But are constant labour market participation rates realistic? If labour markets tighten, won’t supply adjust? Miner seems to make this assumption – not because he thinks it’s true, but because he wants to highlight the scale of the coming transition. As I showed back here (and as Miner himself notes) we have already seen a shift in the employment pattern of older workers: since 2000, employment rates have been rising 1 percentage point per year among 55-64 year olds, and 0.5 points per year among the over 65s. And there’s no obvious reason those can’t continue; even if the current rate of growth lasted twenty years, our post-55 employment rates would still be behind the current rates of New Zealand and Iceland.

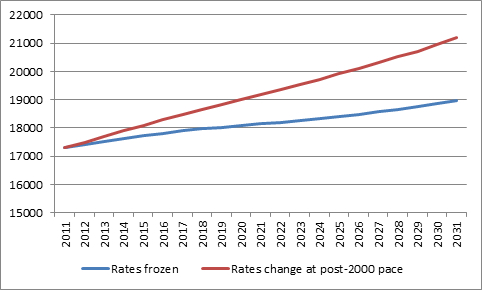

So, what happens if you replace the no-change projection with one based on employment rates continuing to increase at their post-2000 rate? Check this out:

Future Employment Rates, Based on Different Assumptions About Employment Rates Among Workers Over 55

That’s a 2.2 million job gap between the two projections – enough to entirely wipe out Miner’s projected shortage.

To be clear, this projection is no better than Miner’s – we’re both just straight-lining different aspects of current reality. But it does show that the whole “looming labour shortage” meme depends heavily on initial assumptions.

Tomorrow, we’ll look at the policy implications of this.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post