The meme on “underperforming universities” these days revolves around the idea that specific fields of study – usually Bachelor’s degrees in the humanities – do not lead to good jobs. But this depends in no small measure on what one means by a “good job”, and over what time frame one chooses to measure success.

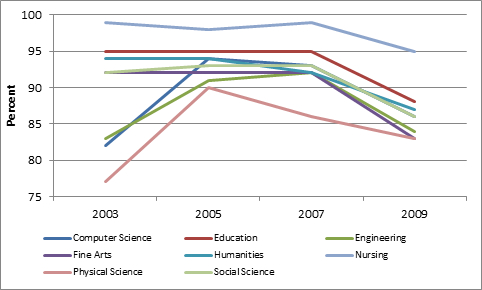

The graph below shows data from Ontario, six months after graduation. Between 2003-2007, the employment rate of graduates in the labour market (i.e. excluding those who chose to study) bounced around between 92 and 94%. In 2009, the rate fell by about 7%, to roughly 86%, more or less equally across all disciplines. Some fields of study were consistently below the average – specifically, fine arts, physical sciences (which seems to include biological sciences), and engineering. Some fields of study were well above the average, notably education and nursing. Humanities and social sciences ended up half way between the two.

Employment Rates of Ontario Graduates Six Months After Graduation in Selected Fields of Study, 2003-2009

The science figure is especially interesting, isn’t it? Makes you wonder why there’s an S in STEM.

Now, some of you will surely be scratching your heads at this point. Aren’t STEM graduates supposed to be in high demand? How are both getting beat by Arts grads? Three quick answers. The first is that these figures exclude people who have gone back to school (unhelpfully, the Ontario data doesn’t tell you how big a number this is). Two is that Engineers may take longer for a job search because they are secure in the knowledge that their eventual job will pay pretty well (see below) – the pattern we see after six months is also the pattern after twenty-four, as the chart below describes. And three is that the picture does change a bit after two years.

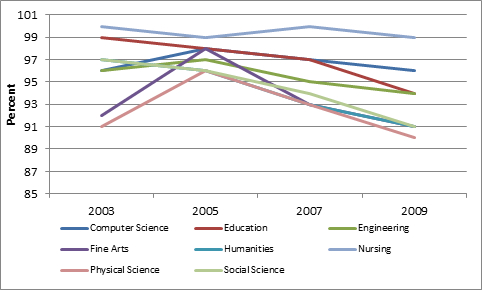

Employment Rates of Ontario Graduates Two Years After Graduation in Selected Fields of Study, 2003-2009

The classes of 2003 and 2005 had 2-year employment rates of about 96.5%. That fell to about 95% for the class of 2007, and 93% for the class of 2009. The fall was concentrated in education, humanities, social science, fine arts, and physical sciences; other disciplines saw less change.

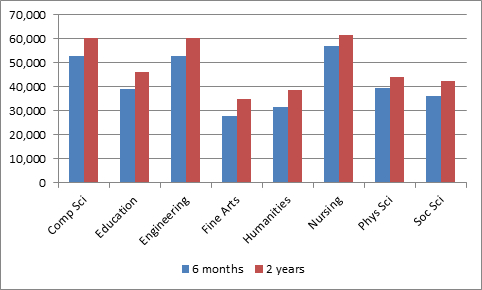

Finally, there is the issue of income. Here you see the real knock on studying in the humanities; it’s not that they don’t get jobs – it’s that they end up in some jobs that don’t pay well. Now, their incomes do increase about twice as fast as others between six months and two years (in the midst of a recession, they jump, on average, by 21%), but they start from a lower base. An interesting point here, which I have made before, is that the difference in outcomes between students in the sciences and the social sciences is negligible.

Income of Ontario University Graduates Six Months and Two Years Out, Selected Fields of Study, Class of 2009

Clearly, jobs aren’t the issue – students of all stripes find work soon enough. The issue is the rate of return. We should focus on that.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Why is it essential that we focus on rate of return for Humanities grads in particular? To be honest, it feels a little like finding a new strategy because the target has proved impervious to the first one: in this case, the humanities post-grad employment rate is higher than its critics expected, so its critics have now decided to attack on the grounds of poor pay.

If your conclusion is that humanities degrees do have a lower rate of return than you’d like, then I for one would be interested to hear which humanities-heavy sectors should be shut down, should be deskilled, or should be forced to pay higher wages. 🙂

Hi Richard.

Surely those aren’t the only three options, are they?

Look, if humanities grads are happy with lower ROIs (financial ROIs anyway- education provides lots of non-monetary returns as well), then I for one have no problem with that. Whatever spins your (their) wheels. From the stuff I hear and read, though, I get the impression that’s not entirely the case – that humanities grads do wish there. So I think it’s worth asking the question: are there things that can be done to give humanities grads more of an edge in the labour market? I suspect that there are, if we care to re-think curriculum a bit.

Of course there are more options than my flippant three, Alex: but as for re-thinking curriculum, two things come to mind.

First, you’ve posted yourself about the genuinely interesting research findings about the weakness of skills-based training when compared to postsecondary education, and I thought somehow that this was a validation of a curricular approach not focused on skills. (But maybe I’m misunderstanding where a curricular re-think, in your view, might lead….)

Second, as far as I know, every single humanities program at every Canadian university is engaged in a curricular re-think, to one degree or another. Most of ours at UVic have just been through department retreats, for example, where we were trying to think about such things as skill-focused learning outcomes, clarity in progress through the degree (which courses in what order to achieve what aim), and connections to employment (such as through co-op terms). We talked about a lot of other things, too, but your phrase “if we care to re-think curriculum a bit” is, if I may, a bit revealing about the extent your disconnect from actual curricula.

I should have put a happy face next to my first sentence, but I really hate emoticons.

It’s quite possible I’m disconnected from curricula. Lord knows I’d like to get out of this office more. But I don’t get the sense from many people that things like co-op are particularly high on the list of most humanities depts (though it’s great to hear that it is happening in some places). I think we’re starting to see a bit of reflection about learning outcomes – but it seems to me there is still a great deal of resistance in terms of casting these in terms that relate to the labor market (which is not at all to suggest they should entirely be about LM – that would be ridiculous).

It seems clear that the humanities and social sciences, as well as the sciences, are valued less than applied science and technology. In Alberta where I live, trades persons make better livings than university graduates in non-technical fields. We need a more interdisciplinary approach to education, where the insights of the humanities and social sciences are valued for what they bring to engineers, computer scientists, electricians, and plumbers. And we do need electricians and plumbers who can make informed choices and enjoy their own minds. We also need scientifically literate graduates in the humanities and social sciences.