One of the rallying calls of part of the scientific community over the past few years is how under the Harper government there was too much of a focus on “applied” research and not enough of a focus on “pure”/”basic”/”fundamental research. This call is reaching a fever pitch following the publication of the Naylor Report (which, to its credit, did not get into a basic/applied debate and focussed instead on whether or not the research was “investigator-driven”, which is a different and better distinction). The problem is that that line between “pure/basic/fundamental” research and applied research isn’t nearly as clear cut as people believe, and the rush away from applied research risks throwing out some rather important babies along with the bathwater.

As long-time readers will know, I’m not a huge fan of a binary divide between basic and applied research. The idea of “Basic Science” is a convenient distinction created by natural scientists in the aftermath of WWII as a way to convince the government to give them money the way they did during the war but without having soldier looking over their shoulder. In some fields (medicine, engineering), nearly all research is “applied” in the sense that it there are always considerations of the end-use for the research.

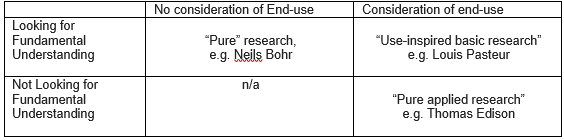

This is probably a good time for a refresher on Pasteur’s Quadrant. This concept was developed by Donald Stokes, a political scientist at Princeton, just before his death in 1997. He too thought the basic/applied dichotomy was pretty dumb, so like all good social scientists he came up with a 2×2 instead. One consideration in classifying science is whether or not it involved a quest for fundamental understanding; the other was whether or not the researcher had any consideration for end-use. And so what you get is the following:

(I’d argue that to some extent you could replace “Bohr” with “Physics” and “Pasteur” with “Medicine” because it’s the nature of the fields of research and not individual researchers’ proclivities, per se, but let’s not quibble).

Now what was mostly annoying about the Harper years – and to some extent the Martin and late Chretien years – was not so much that the federal government was taking money out of the “fundamental understanding” row and into the “no fundamental understanding” row (although the way some people go on you’d be forgiven for thinking that), but rather than it was trying to make research fit into more than one quadrant at once. Sure, they’d say, we’d love to fund all your (top-left quadrant) drosophilia research, but can you make sure to include something about its eventual (bottom-right quadrant) commercial applications? This attempt to make research more “applied” is and was nonsense, and Naylor was right to (mostly) call for an end to it.

But that is not the same thing as saying we shouldn’t fund anything in the bottom-right corner – that is, “applied research”.

And this is where the taxonomy of “applied research” gets tricky. Some people – including apparently the entire Innovation Ministry, if the last budget is any indication – think that the way to bolster that quadrant is to leave everything to the private sector, preferably in sexy areas like ICT, Clean Tech and whatnot. And there’s a case to be made for that: business is close to the customer, let them do the pure applied research.

But there’s also a case to be made that in a country where the commercial sector has few big champions and a lot of SMEs, the private sector is always likely to have some structural difficulties doing the pure applied research on its own. It’s not simply a question of subsidies: it’s a question of scale and talent. And that’s where applied research as conducted in Canada’s colleges and polytechnics comes in. They help keep smaller Canadian companies – the kinds that aren’t going to get included in any “supercluster” initiative – competitive. You’d think this kind of research should be of interest to a self-proclaimed innovation government. Yet whether by design or indifference we’ve heard nary a word about this kind of research in the last 20 months (apart perhaps from a renewal of the Community and College Social Innovation Fund).

There’s no reason for this. There is – if rumours of a cabinet submission to respond to the Naylor report are true – no shortage of money for “fundamental”, or “investigator-driven” research. Why not pure applied research too? Other than the fact that “applied research” – a completely different type of “applied research”, mind you – has become a dirty word?

This is a policy failure unfolding in slow motion. There’s still time to stop it, if we can all distinguish between different types of “applied research”.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Agree strongly with your challenge to the pure/applied binary, but again from a public policy perspective there is another way to frame this debate: the need for more research (and more funding for research) centred on solving specific problems. For example, in Nova Scotia we had unique and persistent challenges on things like the rapid spread of Lyme disease, exceptionally high rates of colon cancer, eco-system based fisheries management and how to deliver high quality public school education to small, isolated rural communities. To address these challenges we needed researchers (or teams of researchers) to generate new knowledge spanning from basic through to policy solutions and “commercializable” innovations. Lots of debate about governments picking winners and losers in terms of economic sectors and opportunities, but much less resistance to focusing resources on imperatives like climate change and clean energy that require new knowledge on all levels.

Many — most? — of Canada’s colleges are located outside of major metropolitan areas and are thus uniquely positioned to offer support to SMEs (which is, let’s face it, the only kind of commercial sector you’re likely to find in rural or mid-sized town Canada). What’s more, if those colleges don’t engage in research into obstacles to increased productivity, better distribution, addressing food security and poverty alleviation strategies, refining the quality of a product, understanding marketing in a hinterland setting, and so on … then no one else will. The big research universities might send someone down the road but the likelihood is, not. Restoring the CCI Fund and recognizing the enormous potential of non-metropolitan colleges is a meaningful investment in applied research, yes, and it’s also an investment in those communities and very real quality of life issues.

I think that Pasteur’s Quadrant is more naturally portrayed as a Venn Diagram. Two circles, one for “fundamental understanding”, one for “end use”, overlapping in the middle.

If it’s going to stick with a 2×2 format, the bottom left quadrant is clearly “Mythbusters”.

Possibly. But then it wouldn’t be a quadrant.

I like the way in which you break down the distinction between “basic” and “applied,” but it isn’t really clear how any of this would apply to research in the humanities. How would somebody working on Dostoyevsky’s view of Western Christianity fit into it? There’s no obvious application, and it isn’t like our hypothetical researcher is discovering fundamental facts about the universe or the meaning of life. I suppose he or she could tie everything back to Russian expansionism or deconstructing western liberalism, but that would just be to become tendentious.

Would the case I’ve given fit in the lower left and, if so, are you calling for it not to be undertaken at all?

Don’t worry Alex, the government (which talks about evidence based policy- and decision-making all the time) has so far shown absolutely no appetite for investing in research. Ask about a response to the Naylor report on fundamental science and it’s a case of extreme crickets. I’d contend there is a key difference between fundamental and applied research. It’s nicely laid out in Chapter 2 of the Naylor report but to paraphrase, it is a damn sight easier to sell a politician or member of the public on a notion of a useful object/device/treatment than it is to sell a promise/dream that may not be useful yet, but it just might be.

Scientists did themselves a disservice 15 or so years ago by promising returns on investment. There’s good data that you get great ROI but it’s neither predictable nor short term. So lets not get hung up on nomenclature, we should be able to agree that strong research and education are good things and should be supported, however they turn out in the end.