So today, my colleague Jaqueline Lambert and I released a paper on how Canadian students view the process of internationalization (you can download the paper here). It’s a mixed bag, frankly.

On the one hand, we find pretty clearly that students buy into the principles of internationalization. They are very positive about the goals internationalization is meant to foster (diversity, more global awareness), and they’re even enthused about how an increased presence of foreign students improves their schools’ prestige. Over forty percent of students say they’ve made a close friendship with a student from another country. Eleven percent of students have already had a period of study abroad, and another seven percent say they have definite plans to do so. All good.

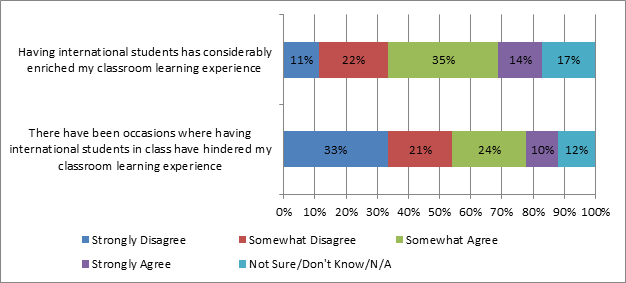

It starts getting trickier, though, where the interests of international and domestic students are not perceived to be aligned. Half of students agree, to some extent, with the statement: the presence of international students in a classroom enriches a learning experience. But fully a third disagree. Similarly, a third of students say that the presence of international students has actually hindered their classroom experience.

Figure 1: Perspectives on International Students in the Classroom.

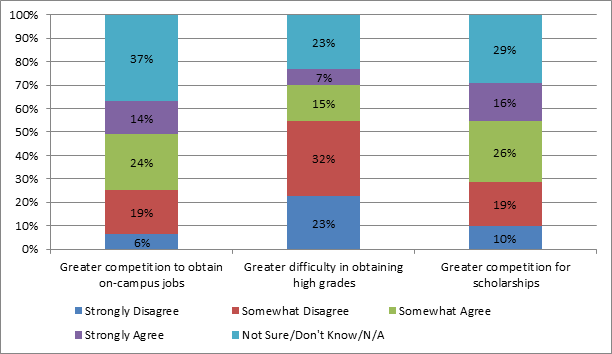

There are also concerns about competition for resources. Thirty-eight percent of Canadian students say the presence of foreign students means greater competition for on-campus jobs, while forty-two percent say it increases competition for scholarship dollars.

Figure 2: “The Increasing Number of International Students Attending my Institution has led to____”.

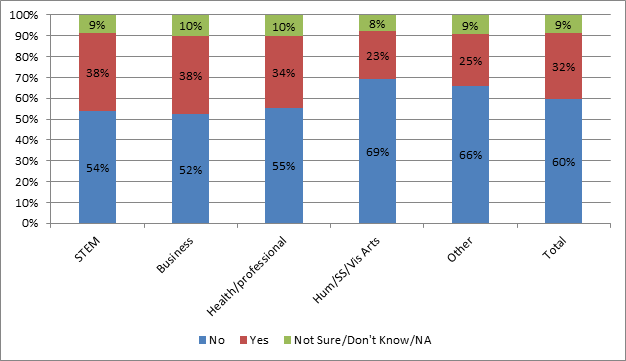

But perhaps the most eye-opening consequence of internationalization has less to do with students from abroad, and more to do with professors. Instructors with a less-than-perfect command of the language of instruction (French or English) are known to be common on campuses, and seven-out-of-ten students in our survey said they’ve had such an experience (more in STEM fields, less in humanities). But when asked a more specific question – has a difficult-to-comprehend teacher significantly hindered your ability to perform or successfully complete a course? – fully one-third of all students said yes.

Figure 3: “Has a Difficult-to-Comprehend Instructor Significantly and Negatively Hindered your Ability to Perform or Successfully Complete a Course?”

Figure 3 shouldn’t be taken to mean that all hard-to-understand professors are foreign, or that foreign professors are hard-to-understand. But there is a significant proportion of instructors – often foreign, often hired for their research ability – who are having a hard time getting their message across to students. And that’s not really OK: students pay a lot of money for their education, and it shouldn’t be too much to ask that their instructors have the necessary language skills to teach them.

What to take from all this? Students remain relatively positive about internationalization, and that’s good. But there are some warning signs here. Not everyone perceives internationalization as an unalloyed good; more attention needs to be paid to the dislocations it causes if internationalization is to continue to be seen in a positive light.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Why the modification of wording been the positive and negative questions in the first chart? This makes the two questions entirely incomparable with each other. “There have been occasions where (sic)” is practically inviting an affirmative response (“well, yes, I remember one time …”), so 54% disagreement strikes me as quite encouraging as to students’ perception of the international students in their classes.

That caveat aside, I am glad to see attention paid to understanding how our campuses are changing. We need to continue existing efforts and new initiatives to ensure effective teaching and learning in our classrooms.

Hi Ryan,

It’s basically because they genuinely are different questions. Disagreeing with “did you have any positive experiences” might not mean that you’ve had any negative experiences, it could just mean that you’ve not had any experiences at all. So we felt it necessary to ask a question in each direction. The numbers ended up actually looking pretty similar so maybe we didn’t need to do that, but that’s where our heads were at at the time.