Here’s a story you might have heard about access policy in Scotland: the (right-wing, neoliberal) Labour government of the late 1990s imposed tuition fees on Scottish students and students were very hard done by. About a decade later, the (lefty, progressive) Scottish Nationalist Party government abolished tuition fees and everything was suddenly a student paradise. You may even have heard about the commemorative stone the ex-SNP First Minister Alex Salmond had installed at Heriot-Watt university bearing the words “The rocks will melt with the sun before I allow tuition fees to be imposed on Scotland’s students” (yes, really).

But this isn’t quite accurate. Not only does it leave out a couple of key points, but it is catastrophically wrong about impacts. Here’s the real story.

In 1997, back before Scotland came to have a separate parliament, the UK as a whole implemented tuition fees of £1,000 per year or £3,000 over the course of a degree. But they were a very specific kind of tuition fees: they were income-targeted. Your family earned less than (roughly) $40,000? You didn’t pay. Partial fee exceptions were available up to around $55,000. Then, in 2001, the Labour government of the newly-devolved Scottish government changed that to a £2,000 graduate “endowment” fee, payable upon graduation (drop-outs paid zero) either in cash or by adding it to one’s student loan. Most students did the latter and so Scotland’s system for the next few years particularly resembled Australia’s HECS-HELP system, only with much smaller required repayments. Labour also re-instated maintenance grants (i.e. bursaries for living expenses) which had been cut a couple of years prior.

Then the SNP came to power and abolished this “endowment”, which they (not entirely unreasonably) insisted on calling “tuition”. But this “tuition” they abolished was not up-front tuition. No one had to pay a cent up-front. The only people that had to pay were those who had graduated and were making money: otherwise, the obligation to repay was zero. The only possible argument against this system – from an access point of view, – was that the fear of debt, even if it was totally conditional on completion and income, might make someone think twice about undertaking an education. It’s an argument that doesn’t make a whole lot of sense to me, but it’s an argument.

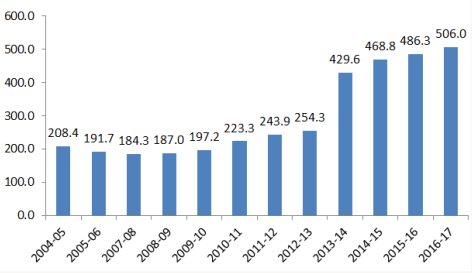

But then, how to explain the SNP government’s actions in 2013? For that was the year when, faced with the need to make budget cuts the government decided to…cut need-based grants for the poorest students and switched them on to loans instead. Result: borrowing doubled, and kids from the poorest backgrounds are now regularly ending up with over £20,000 in debt, or slightly more than the average here in Canada.

Figure 1: Annual Student Borrowing in Scotland, in millions of pounds

Source: Lucy Hunter-Blackburn, https://adventuresinevidence.com/2017/10/31/20542/

Now, I suppose you could engage in some titanic whattaboutery, and say oh but look how indebted English students are with their £9,000 tuition and excessive debt, etc, but that would be spectacularly beside the point. There are positions on the dial between “free tuition” and “£9,000”. And if the entire point of “free tuition” was to reduce debt, then it’s more than passingly strange that your next big policy move would be to pile more debt on to the poorest. I mean, it’s even weirder than the Alberta government going on about tuition freezes while co-incidentally having the weakest need-based grant programs in the country.

The SNP had the option to ask richer kids for tuition. Go back to the 1997 system where contributions were asked of kids with wealthier parents and nothing was asked of kids from poorer families. But no. The SNP instead deliberately decided to spare kids from wealthier families from paying an extra cent, and meanwhile told poorer students to go and take on additional debt. I defy anyone to explain to me how that’s progressive.

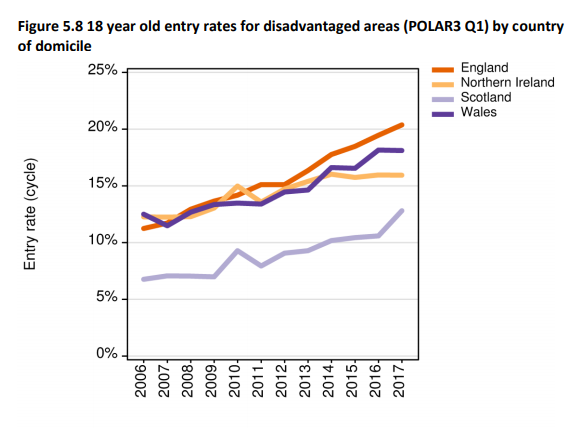

And of course there’s a final question: did “free tuition” actually improve the lot of low-income students in Scotland? Well, let’s check in with the UK’s University and Colleges Admission Service (UCAS) End of Cycle Report, which tracks applications and acceptances by socio-economic class and jurisdiction. Here’s how various bits of the UK compare with respect to poor students coming from secondary school:

Ignore the absolute gap between Scotland and the rest because a portion of Scotland’s higher education (HE) system – the bit in which people take HE courses in non-university institutions – does not use UCAS. Look instead at the gap in entry rates for poor students between terrible, neo-liberal England and cuddly free-tuition Scotland. It grew from five percentage points to eight. In other words, free tuition did not result in uniquely better access for poorer students: other policies seem quite capable of delivering the same or better results.

But it’s OK. At least wealthier families don’t have to pay anything. I guess that’s what matters when it comes to being progressive in education finance.

If you want to follow Scottish access policy more closely, go no further than Lucy Hunter-Blackburn’s blog “Adventures in Evidence”. It’s excellent.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post