Last week, Statscan published a paper by Marc Frenette (their best education analyst by a country mile) called Are the Career Prospects of Post-Secondary Graduates Improving? The results are interesting, but unfortunately the paper doesn’t really answer the question in the title.

The paper compares the fortunes of two groups of Canadians: those who were 25-34 at the time of the 1991 census and those who were the same age at the time of the 2001 census. It then follows each of them using tax data for the next 15 years (ie. until the ’91 cohort was 40-49 in 2006 and until the ’01 cohort was the same age in 2016). From a data quality standpoint, this is about as good a data sample as you are going to get: everybody who filled in the census in those years and who filled out a tax form every year for the next 15 years. No sampling, no surveys: just pure high-quality admin data.

Let’s get the critique out of the way first. This study tells us nothing about anybody who had graduated from post-secondary in the last twenty years. If we assume average graduation age is about 23, then the very youngest people in the more recent cohort graduated in 1999; the oldest people in the earlier cohort graduated around 1980 (the average grad years of the two cohorts were about 1985 and 1995). So, whatever this data is telling us, it’s not about millennials or even really the latter half of Gen X. Avoid drawing conclusions re: the present day.

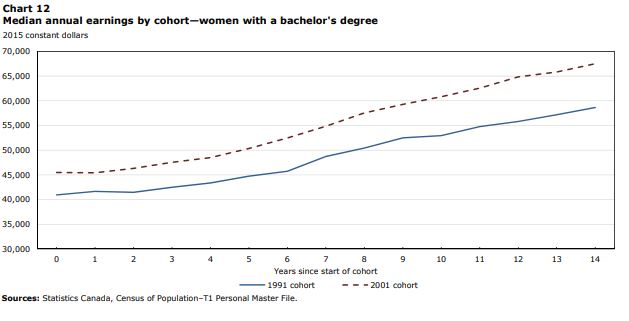

That said, though, the comparisons are interesting. Average educational attainment levels rose significantly during the 1990s. For instance, 15.8% of the 1991 cohort held a bachelor’s degree, compared to 31.7% in the 2001 cohort. One might therefore suspect that the 2001 cohort would have slightly lower incomes, adjusting for inflation, because there are more people competing for the same jobs. But in fact, that’s not what we see at all. The figure below is for women with bachelor’s degrees, but the story is the similar for men and across all levels of education from college upwards: despite the big increases in educational attainment, the 2001 cohort was about $5000 per year (a bit less for men) better off than the 1991 cohort.

So, great, right? Things are getting better? Well, hold on. It’s really hard to know how to interpret this because of how odd the cohorts are. On the one hand, it’s easy to say “oh well, the 2001 cohort had it easy because it graduated into good times (which was more or less true of everyone except Engineers), while the 1991 cohort graduated into the worst economic crisis since WW2”. And if that were true, it would be enough to throw some shade on the results; as Frenette himself notes, there has been some interesting research on the permanent income “scarring” effects some cohorts experience when they graduate into a bad labour market (for instance this work by Phil Oreopoulos et al).

But these aren’t actually cohorts, per se; they’re each groupings of about a dozen different graduating cohorts thrown together. Yes, 2001 was a lot better than 1991, but some of the 1991 grouping would have hit the labour market in 1985 (which, on the whole, was a decent year), while some of the 2001 groupings might have graduated as early as 1990 or so (which was, as we have already noted, a truly godawful year). Frenette goes to some trouble to try to compare the levels of scarring the two groups have, but even so it’s very difficult to conclude much because the groupings are so messy.

I would tend to interpret these results pretty narrowly: they certainly show that 90s graduates on the whole did better than 80s graduates over the long-run, despite higher attainment rates and (in theory) greater competition for graduate jobs. In all likelihood, that tells us something about the overall tendency of the labour market to require and reward higher levels of skill (which is a good thing!) but it also probably is at least partially reflective of the fact that the 2000s were a much better time to be a 30-something than the 1990s were, and not just because it was possible to go many years at a stretch without having to listen to Ace of Base or Hootie and the Blowfish. And in any case, it tells us nothing about cohorts/groupings since 2001.

So: it’s technically a very good study (like I said, this is Marc Frenette we’re talking about) which makes interesting use of new data linkage opportunities, but its generalizability is necessarily somewhat limited. Use cautiously.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post