You may have read recently about how Canada is really sticking it to junior researchers. Dalhousie’s Julia Wright recently wrote about Canada haemorrhaging early-career research capacity and she has a point – just in the last seven years, the proportion of Canadian faculty aged 40 or less has fallen by a third, from roughly 22% to just over 15%.

The question, of course, is “why”? Some – including Wright – just blame a “shrinking academic labour market”, which tends to (either by accident or design) play into a narrative of “terrible neo-liberal governments/university administrators not spending on academics”. But this simply isn’t true: total spending on academic compensation rose 12% after inflation between 2010-11 and 2015-2016, and in fact the number of full-time academic staff at Canadian universities has increased by 1.6% since 2010-11. Some simple math tells you that by extension, pay per full-time academic staff increased by about 10% after inflation over those years. That’s money which, in theory, could have been spent on hiring more staff.

And there’s a very specific place where that money is being spent. It’s on profs over the age of 65.

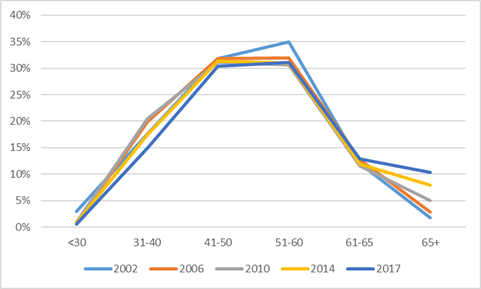

Take a look at Figure 1, which shows the age profile of academic staff at intervals between 2002 and 2017 (data is from Statscan’s UCASS survey, except for 2014 when it is from the National Faculty Data Pool). At most points along the curve, the distribution looks pretty similar in every year – until you get to the over 65s. And here there’s been an absolute explosion in numbers over the past few years. In 2002, they were less than 2% of the (much smaller) professoriate; the most recent UCASS data suggests that this year they make up 10.3% of total professoriate.

Figure 1: Age Distribution Profile of FT University Academic Staff, Canada, 2002-2017

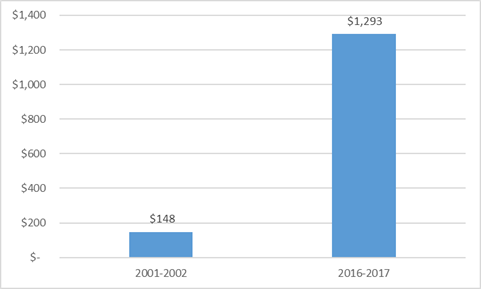

Again, just do some simple math. The over 65s, by and large, get paid substantially more than the average academic. We don’t know exactly how much more, but a fair guess, based on both salary and (much more heavily used) benefits, it’s probably about 50% above average. That implies that about 15% of academic compensation – or about $1.3 billion/year is going to over-65s. Compare that to the approximately $148 million that universities were spending on the same population fifteen years ago.

Figure 2: Estimated Compensation Devoted to FT Academic Faculty 65 Years of Age and Up, 2001-02 vs. 2016-17 (in millions)

That’s a nine-fold increase. A billion-plus-dollar increase. And you know what they say – a billion here, a billion there, pretty soon you’re taking real money.

Now, there’s nothing intrinsically wrong with employing older faculty. No one magically loses energy and vitality and a sense of engagement when they hit the age of 65. But, first, there are opportunity costs – that $1.3 billion could be used to hire an awful lot of new faculty (roughly 10,000 or so, by my count). And, second, I think if you polled academic staff, while they would agree that over-65s can make great contributions, they would also tell you that over 65s are probably somewhat more likely than average to be coasting.

Of course, thanks to the end of mandatory retirement, there’s isn’t a whole lot anyone can do about this. Nowadays, staff can’t be asked to retire even once they are past the age (71) when they are legally required to start drawing their pensions, meaning they draw both their salary, and their institutional pension, and their public pension, plus whatever they have in their RRIF.

In theory, it should be possible to nudge some faculty out – especially those over 71 – by instituting measures which are related to length of employment but not to age per se because that’s verboten. Say, sticking lifetime limits on sabbaticals, or requiring higher teaching loads for individuals who have been employed for more than 30 years. In theory, this should be to the benefit of both academic staff and management, especially if accompanied by provisions guaranteeing a certain number of new hires with the proceeds from any retirements. At the very least, it’s something that needs to be on the table. Faculty renewal depends on it.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

I think your financial view could have a broader context. In my case, between 2010/11 and now, university revenues have increased by $140M (not inflation adjusted), in part by increasing the number of students by 2600, close to 15%, but faculty numbers have remained roughly the same (there have been retirements and replacement, as we have expanded engineering, with, aha, higher tuition fees). During the same period, total university salaries and benefits have increased by $50M (also not inflation adjusted), including the aging faculty effect, but also significant growth in administrational staff. Interestingly and finally, during the same period, the “internally restricted” funds (not allocated in any real sense: no spending, contribution, transfer plans/commitments) have grown from under $20M to over $320M. Yes, the administration appeals to actuarial alchemy to explain some of the set asides, future benefits and pension contributions, but money almost never gets transferred out of these buckets (and even when a bit does, it is replaced by much more). So, sure, the aging faculty effect will account for perhaps $10M of the salaries and benefits increase in the period, and, yeah, $10M could hire 100 fresh faculty members, but there are many other ways to find even more than $10M to fund new hires, including: use part of the $50M increase in tuition revenue, shake one of the “internally restricted” pots to liberate 3-4% of the leprechaun’s gold.

eeeeeesh borderline ageism Alex! How about some population numbers, aren’t we just getting older as a country? We have a record high proportion of 55-64 year olds in Canada, so more of us oldies who pay taxes, mortgage, kids and grandkids tuition etc. will continue to work.

Hi Alex – I think there is a lot more research needed on this.

1. I suspect that the average age at which people are hired into a first tenure track job is also increasing, although likely varies by discipline. I completed a PhD at age 26 and was hired at 30 as assistant professor. Having just reached 65, I have had 35 years to accumulate pension and investments to fund my retirement. People who take many years of poor pay (as temporary instructors, post-docs etc) before achieving a well paid secure position are going to have to stay longer.

2. My experience as provost is that age doesn’t have much to do with productivity. I saw many older faculty members who continued to perform well as teachers, researchers and mentors. In fact, some of the most innovative teaching and program development came from people who could risk failure because they had established their reputation and proficiency as young and middle-aged scholars.

3. People are healthier and living longer, so why retire at 65 if you’re still happy working and making solid contributions?

4. You should take a look at lifetime earnings, not just end-of-career salary. Few professions have such a high age at entry and such a slow ramp-up to top salaries.

5. Some (most?) universities have developed creative programs that allow senior faculty to “phase in” to retirement. For example, SFU allows one to negotiate a part-time role for up to three years, provided that one signs off on a definite retirement date. And at least one SFU Faculty provides some support to retired faculty members who wish to continue their research. We probably should listen harder to what senior faculty need in order to make this transition.

6. And also take a look at the data on actual retirement ages. We may have a lot of 65-year-olds, but I think many people are choosing to retire at about 70, partly because of federal requirements re use of retirement investments.

Merry Christmas!

Jon

A key is retirement income. As pensions are switched to defined contribution plans from defined benefit, people need a shorter retirement and larger nest egg from which to develop an annuity. In the good old days of defined benefit all was well. But with interest rates at all time lows for the last 8 years or so, the prospect of retirement was not as rosy at 65 as it had been for the previous generation. Cutting off five years or so from the pension pay out makes a tangible difference.

Alex’s data show that the abolition of mandatory retirement in 2006 took time to have an effect on faculty members in Ontario. There was only a small increase in the post-65 faculty up to 2010. I think this was because those faculty members who had lived their careers expecting to retire by 65 still did so. They had psychologically committed to it, and had made their plans. But the end of mandatory retirement led to a new way of thinking for those who still had 5 years to go in 2006 and began to realise that they did not need to leave if they did not want to. I agree with Chris Burn that they began to worry about pension income. In other words, concerns gradually shifted from “I want to have the time to enjoy my retirement and so I’m going early” (we still have early retirement in our collective agreement but only librarians take advantage of it) to “I’m worried that I might outlive my pension” (defined contribution plans) or “my pension may be not be large enough in 20 years time” (defined benefit plans). This is the baby boom generation (I’m one of them) and they think they will live forever (or till 100, whichever comes first).

The end result that I saw – in a Faculty of Arts – is that professors wanted to continue to draw their salaries and increase the size of their pension through additional years of employment. For some (perhaps many), being a professor was also a crucial part of their identity. They retired mainly when they or their spouse had health problems, which meant that their retirement would then not be what they had been awaiting. Pretty sad when you think about it.

Alex is right that these changes have had a significant impact on budgets. The whole progress-through-the-ranks model at my institution which is meant to be zero sum, falls apart if professors reach the ceiling and then stay employed for a decade or more, not only blocking new hires, but moving the salary mass upward. Alex’s solutions to “nudge” out the post-65s are creative. Whether the unionized professoriate would accept them during negotiations and whether they would withstand the first human rights challenge is another matter.

I didn’t have to read beyond the first couple of paragraphs to know where the problem is. I see a number of older faculty members coasting and collecting huge salaries as well as pensions, and at the same killing morale in the departments where they languish. I agree with a previous comment that some older faculty do remain productive, but those who are not should be shown the door. We wouldn’t give unproductive faculty tenure or promote them, why should they be allowed to prolong their careers well beyond their best-before dates? We have mechanisms to remove unproductive faculty – regardless of age – and these should be used more often.

“Sticking lifetime limits on sabbaticals” would only make things worse, since sabbaticants take a pay cut when on sabbatical. No sabbatical = no pay cut = increased cost to university.