The Canadian Association of University Teachers (CAUT) put out a paper on Tuesday entitled Out of the Shadows: Experiences of Contract Academic Staff, which mostly presents data on a survey conducted by the association last year. While the intentions might have been good, the resulting data – which is already getting lots of media play – needs to be taken with a grain of salt. And one claim in particular – that the number of sessional faculty has soared by 79% in the past decade – needs to be debunked immediately.

While the survey instrument itself is mostly OK (biggest quibble: no way to identify which respondents were also grad students), the reporting of the data is not great. It’s mostly univariate results when cross-tabs would have revealed a lot more interesting stuff. When bivariate data is shown (eg. desire for tenure-track appointments vs. length of PSE teaching career) aggregate totals are not always shown and it’s not always clear how many people are actually in each category. Sometimes, the data is just wrong (for “highest level of education”, the categories add up to 123%). Most annoyingly, the authors for some reason did not report the answers to question 17 of their own survey, which asked how individuals self-classified (contract instructor who teaches part-time/FT, professional who teaches part-time, graduate student with teaching responsibilities, etc.). That would have been very illuminating, but one suspects the results might not have served the report’s agenda well.

The bigger problem – one the report’s authors do note at the outset but perforce tend to ignore in the conclusion – is the limitations of the survey’s sampling strategy. This is not the authors’ fault: building a good sample frame is virtually impossible to do given universities’ reluctance to participate in these kinds of exercises (which, frankly, is ludicrous and harmful). So, what you’re left with is a sample acquisition strategy which can best be described as “emailing a survey invite to everyone associated with CAUT and putting it up on Facebook and Twitter and hoping people respond”. This strategy produces some unacceptable response biases. Normally what people do with these sorts of samples is they make some kind of attempt to at least re-weight the sample against known quantities to make it approximate the underlying population. Admittedly, this is difficult to do in the case of sessionals because the entire problem is that we can’t say anything about the underlying population, but even a casual look at the demographics shows it’s overweight for Ontario and the humanities and underweight for Quebec and business and engineering. It’s also – compared to the one piece of very good data we do have on sessionals, published by COU back in January – overweight on people with terminal degrees. Re-weighting the survey somewhat in all those directions would have delivered a more credible result. But again, the results might not have served the report’s agenda well.

“Alex”, I can hear you say, “you keep banging on about the “report’s agenda”, what makes you so sure there is an agenda?” Well, first, it’s a report put out by a stakeholder group, so there is certainly an agenda. Interests gonna interest. But the giveaway is actually in the introduction, where the authors make a claim about the increase in part-time staff numbers which is so obviously wrong that it’s very hard not to see a deliberate intention to deceive.

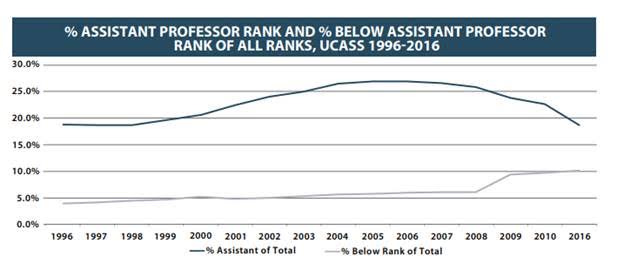

The problem is the interpretation of the graph, below, on page 7 of the report. The labelling here is almost accurate (Checking the Statscan data, I think the “below rank” total actually includes both “below” and “other ranks not classified). But the interpretative text immediately above it is seriously problematic.

Here’s what the authors wrote:

Statistics Canada’s University and College Academic Staff System survey (UCASS) data suggests that over the past twenty years, the number of assistant professors in Canada peaked around 2005-2006, while the number of professors without rank increased. Even these figures are muddied by the fact that some Limited Term Appointments are classified as Assistant Professors. However, by noting this limitation, we may assume that the percentage of permanent positions, ranked at Assistant or higher, has dropped even more significantly, relative to lower ranks, than the available statistics tell us. The drop in full-time, full year positions is also evident in the Census which shows a decline of 10% from 2005 to 2015. During the same period, university professors working part-time, part-year increased by 79%. (emphasis is on the original).

First of all, counter-pointing rising numbers of (alleged) sessionals with a fall in the number of assistant professors in Canada is amateur-hour data cherry-picking. The reason the number of assistant professors fell is that THEY GOT PROMOTED. If you look at total full-time academic positions, those numbers have remained constant or grown. This isn’t rocket science: people have been writing about the effects of the end of mandatory retirement for professors and the implications for faculty renewal for years (for instance, here): ignoring this literature suggests you have a definite motivation for not wanting your readers to remember all that inconvenient stuff.

But, second, and more importantly, “ranks below professor” cannot mean “part-time, part-year” the way the authors claim because UCASS doesn’t track part-time professors. Rather, what it means is ranks such as “instructor”, or “lecturer” or other terms given to tenured or tenure-track faculty who are teaching-stream; if we include “other ranks” in there, it also includes faculty at places like Kwantlen Polytechnic and Vancouver Island, which do not use academic ranks.

And that “79% increase”? Nearly all of it occurred between 2008 and 2009, which just happens to be the first year a whole bunch of former colleges in Alberta and British Columbia – some of which do not use ranks and others of which are big users of teaching stream faculty – became included in UCASS data as “universities”. Had anyone bothered to check the data, they would have found that 1405 of the 1633 new staff with “below assistant” or “other rank) in 2009 – that is, 86% – were employed in those two provinces. So that 79% increase number is utterly wrong, based on data which is both misattributed and misinterpreted. Don’t quote it, don’t use it, let’s kill this zombie stat before it gets properly animated.

But there’s a bigger problem than the stat itself. There are a lot of people in CAUT who should have known this data was wrong when it was published. Frankly, no one understands the data about academic ranks better than the people who publish the excellent CAUT Almanac. So the question is: did the quest to publish a stat that sounds good get in the way of publishing good sound stats?

I’d say it looks like it. And that’s a problem for CAUT’s credibility which goes well beyond this document.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post